I came to Tamaki Saitou's Beautiful Fighting Girl with the expectation that it would answer the question I have pondered on for a while now: why does anime have so many "combat" girls? I left somewhat disappointed. The unfortunately abbreviated BFG was, if the translator's opening blurb is to be believed, the first in a opening salvo of critical academic writing on the subject of anime, manga and the subculture of otaku, much of it yet to be translated.

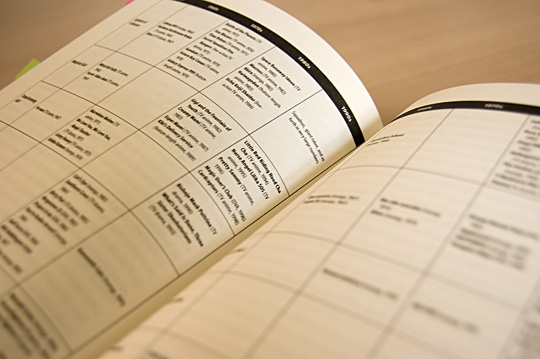

Many of my grievances with the actual text are covered by Brian Ruh's overview which also concisely summarises the content of each chapter. It's hard to believe, but the meat of the book is only contained within the final two. The first orders the various different types of fighting girl into a taxonomy according to their use in anime, manga and live action films from the 1960's onward. The second explores how the beautiful fighting girl paradigm came about.

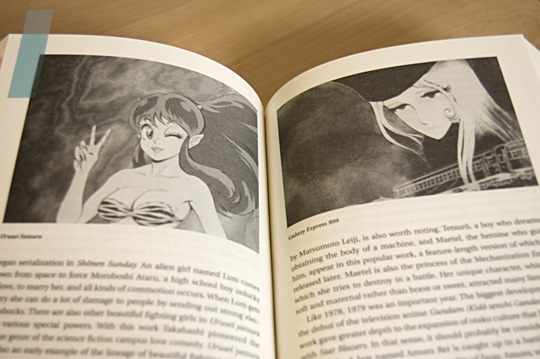

Anyone with any familiarity with anime will be familiar with the typical presentation of a beautiful fighting girl - pretty, naive and a little klutzy but can sling magic and high kicks with the best of them. Fighting girl royalty includes Sailor Moon, Cutey Honey and more recently Shana and Nanoha. Glossing over the nuances the book covers - the beautiful fighting girl is as a grand archetype is tied to two core concepts: how otaku consume anime and manga, and what comes from what the author sees as a split in the way fiction is approached by the West (Europe and Northern America specifically) and Japan.

Otaku consumption

Otaku interact with media - anime and manga - in a different way to other non-otaku. It's generally agreed that this boils down to being able to "own" a fiction (story, character, genre etc.), commonly achieved by writing fanfiction, drawing doujin art, perhaps writing a blog or simply to discussing it with friends. This ownership is tied to the idea that otaku can "context switch" without think, so when watching a show or reading a manga they are interacting (cataloguing, pattern matching, internalising) with the fiction of that media differently than they would, for instance, socially with other people or during their day to day lives. Saitou shotgun-blasts several different meanings of "reality" which is often baffling and frequently contradictory and is perhaps the keenest place where the translation from Japanese isn't ideal.

This turns the idea of the socially stunted loner stereotype of the otaku that is commonly championed on its head and it's easy to see that when this "switching" doesn't happen is when the much reported extremes happen e.g. "2D over 3D", hikkikomori (be sure to read Shutting Out The Sun by Michael Zielenziger for more on the latter). But what does this have to do with a beautiful fighting girl? In short: her unreality, the very fact that she can't as a character or personality exist within the real world, is what makes her desirable because it allows a viewer to "own" her fiction very easily. Perhaps because of the inherent ephemerality there is a sadness to her existence which only increases the desire, to keep her "alive" longer than the fiction otherwise would allow.

Saitou discusses the Western counterpart to the fighting girl, portrayed as "warrior women". Older than the youths that are anime staples, their raison detre is commonly a trauma that defines them and pushes them to fight. For instance, Revy from Black Lagoon and Caska from Berserk would both fall under the warrior woman paradigm as they've both suffered trauma in their past - the former from an abusive father, the latter a randy regent. Juxtapose them with Reina from Queen's Blade who fights, simply because the plot demands it and is never sullied by revenge or hatred. That age difference is commonly seen in anime as a negative - the mature woman antagonist for instance opposing the more righteous youth - and is suggested that the "transformation" part of magical girls is an analogy for (temporary) maturation - an interesting idea when considering transformations that include gender switching (Ranma 1/2, Kämpfer).

Saitou does admit that fighting girls do exist in the West but in smaller numbers. Prime examples include Kitty Pryde from the X-Men comics or more recently Hit-Girl from Kick-Ass or even Hanna from the self-titled 2011 film.

The author refers to the beautiful fighting girl as a "phallic girl" and dives into the idea of them being "hysterics" which, although I'm dimly aware of the pschoanalytic meaning behind both terms, still cut too far into what is already a sexist minefield, especially when considering the Saitou's negative view on homosexuality or the refusal to deal with non-heterosexual male otaku.

East vs. West

The second element to the beautiful fighting girl paradigm is the perceived split between fiction in Japan and the West. In broad strokes: Western fiction by and large has a large number of different core stories and genres but little modification of presentation, Japan and anime/manga meanwhile have few core stories but much variation in how they are told. It's an abstract idea but at its heart is the idea of fantasy - Japan tends to revel in tearing away from reality as often and as early as possible, whereas the West favours an anchor in reality.

The best analogy I could conjure for this was the lack of "other world" type shows in the West such as Escaflowne, Magic Knights Rayearth etc. It has a nugget of truth to it but the cut and dry version presented by Saitou falls down under even cursory scrutiny.

Regardless, when this is used to define the beautiful fighting girl, the argument is that the reverence for unreality and theatre allows and even encourages acceptance of her desirability. That unreality is inherent to the presentation of both manga and anime and extends into what was once science-fiction with Sharon Apple from Macross Plus or Idoru by William Gibson: when the last remaining human component, the voice actor, is virtualised, the desirability remains as can be seen with the phenomenal popularity of Hatsune Miku.

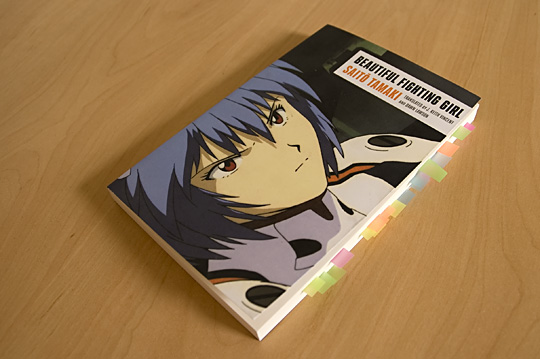

Saitou refers to the difference between the two different approaches to fiction as Western and Japanese "space" and likens the Japanese space to Takashi Murakami's superflat illustrations - an argument the original Japanese publication took to heart with a cover by the artist; the English translation meanwhile only sports a fierce looking Rei from Evangelion. Odd as Evangelion is only ever obliquely referenced as a kind of academic discourse monolith, casting a long shadow and spurring even the most disbelieving of psychoanalysts to write.

Issues

Beautiful Fighting Girl was first published in 2000 and since then a sea change in the way anime is viewed and consumed has taken place thanks largely to the internet. Saitou's book is obviously unable to cover the "moe" boom that is still washing up debris even now. But the best of ideas and analysis are always timeless and I have fundamental issues with the way the author argues for the beautiful fighting girl.

The primary one, and is entirely attributable to the author's academic specialisation, is the defaulting to sex as the great underpinning force behind everything. The opening chapters even go as far as to define otaku as bluntly as someone who can masturbate to images of anime or manga. It's not a radical view when one ponders the multifarious perversions perpetrated by sites like the rightly maligned Sankaku Complex, but it's a rather bleak outlook on a subculture which has always had far more nuance to it regardless of the definition. Indeed, the subtext to his interpretation of a beautiful fighting girl is little more than a template to be fiddled with sexually (literally and figuratively) in order for otaku to attain ownership.

Similarly Saitou claims rather brazenly that Hayao Miyazaki (of Studio Ghibli fame) has such a wide range of young, strong female protagonists in his films (Nausicaa, Mononoke etc.) because of his underlying sexual feelings ("trauma") towards the fictional heroine of first anime he saw: The Tale of the White Serpent. It's a bold statement and though probably academically justified, just feels flat-out wrong when referring to one of the foremost creators of progressive, de-sexualised female protagonists.

Ideas and further reading

As is so often with books like this, the best aspects are between the lines and come in the ideas it seeds and discussion it fosters rather than the text itself. It's somewhat of a shame that the extensive discourse that resulted from this book isn't available in English, however the publisher of this book has already released the widely regarded Otaku: Japan's Database Animals - a thankfully a more accommodating read for the less academically specialised - as well as the dense essay collection Robot Ghosts and Wired Dreams (which itself contains an essay by Saitou) and the diverse Mechademia series of books.

At best then Beautiful Fighting Girl (Sento bishojo no seishinbunseki) is a touchstone of a time when straight faced discussion of anime and otaku was still rare. It sporadically shows brilliance in incorporating diverse topics into the discussion such as the "Comics Code Authority" and its neutering effect on Western (American) comics, or touching upon the distortion of time in both manga and anime, most recently epitomised by Redline, or even coming up with the wonderfully succinct "campus love comedy" definition for the unusual girls at school genre (Ah! My Goddess, Tenchi, Uresei Yatsura et. al.). At worst though, it's an offensively sexist, protracted dive into a well-regarded psychoanalyst's meandering thoughts, more focused on defining otaku and examining obscure outside artists than getting to the core of what the book is ostensibly about.

Other reviews of note:

Nina Cornyetz

Bodies in Movement

I'm just curious to see what Tamaki's views would be in the uprise of technological culture involving Vocaloids and esp. Hatsune Miku. Probably would defend like he did with all the otaku, but it's still an interesting change to see.