First released: April 2013

Version reviewed: TV

I’m going to jump right to it and say that I enjoyed the first series of Attack on Titan.

With that out of the way: the dilemma when talking about something as popular as Shingeki no Kyojin (Attack on Titan) is that at a certain point you start talking around it, probably about things that can be prefixed with “fan”: be that art, fiction or just vocalness. This isn’t a problem specifically with the anime itself but that the series became an event. It reached critical mass with hype and viewer numbers meaning that if you watched it and were online at the time it first aired, chances are you were taking part in the grand event that was Attack on Titan rather than just watching the show.

The vociferousness of the series’ fans, depending on your viewpoint, is balanced with those rallying against it. Condemning it along with other popular series (Sword Art Online is a common partner) as “baby’s first anime” or for people who don’t know “good” anime. Reductivism would be the easiest retort: oh these sounds and images being interpreted by my brain regress my intellect? But when it comes down to it, I don’t much care about the intelligence of the gladiators on display, as long as they put on a good show. And, for the most part, Attack on Titan does.

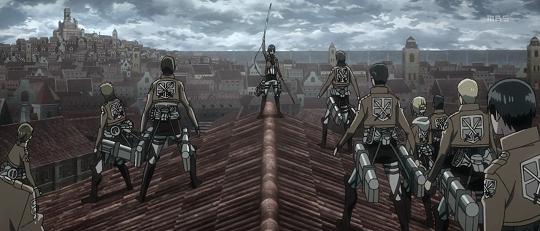

It has all the bluster and pomp that goes along with something that publishers are almost certain will be popular; when a production, whether that book, film or series, becomes an event money follows and, in this case, a significant amount of that money is up on the screen. Whether it’s glorious evening skies, sweeping walled cities or the titular giants stumbling across the landscape, Production I.G. subsidiary Wit Studio have lavished as much detail on the medieval, pseudo-European setting as the crystalline eyes of protagonist Eren. Accompanying this are the chunky line work and distinctive art style from the manga source that are handled confidently, if not entirely consistently. Indeed, indicative of the production as a whole the series noticeably sags during its quieter moments.

When the grotesque giants of the title aren’t devouring the populace or generally visitng destruction upon the remnants of mankind, it’s left to the characters to fill the calm. And with notable exceptions, none of them can manage despite the sheer number of them.

Out of the core trio - Eren, Armin and Mikasa - it’s Armin that shows the most progression and the most humanity from start to finish. Eren on the other hand, take pity on his voice actor Yuuki Kaji, because the majority of his myopic, frenzied dialog is screamed over the sound of how unfair life is. His childhood friend, Mikasa, a beautiful and rare member of her race (read: Japanese) is stoic, ruthless and wholly devoted to safeguarding Eren, meaning the majority of her dialog comes from her overbearance towards him. This leaves Armin to pick up the slack going as he does from cowardly weakling to cowardly strategic genius.

The multitude of other characters are painted with broad strokes - a tortured pragmatist here, a Napoleon complex there - and the series isn’t skilled enough to really explore them. This is especially noticeable with the latter half’s antagonist who is even more taciturn than Mikasa and despite brief glimmers of a back story, remains a cipher right through to the somewhat abrupt end. Character development as a whole suffers because it attempts to use the same tricks that pad out the action sequences: copious flashbacks, time dilation, prolonged introspection… It’s only just tolerable there, so having protracted scenes where a lot is spoken but little is said doesn’t really provide any insight or foster any empathy with the cast.

For the action itself, the frequent cuts away from the present annihilates the pacing and along with “previously on” segments kicking off each episode, serve only in structuring the series so that you can’t just watch one episode. Like popcorn you have to have more and the urge to just plough through every episode is a test of willpower. Watching it week on week, like many shounen shows, must have been excruciating.

What you get in return though are two story arcs - the “You’re a titan hunter now Eren” arc and the “Crikey those are big trees” arc - and a lot of fresh situations to forge heroes out of. So after the mercifully short initial spin up - titans, towns, trauma, training - it’s straight into the kind of imaginative savagery that becomes the series trademark. Aided in part by the utterly ludicrous “3D manoeuvre gear” - what Spiderman would wear if he were into bondage and steampunk - the soldiers zip about towns and forests like angry wasps with a kineticism and a reckless disregard for physics. That is until they encounter one of the titans. At which point they usually become little more than speed lines and a red smear as they are bent, squashed, broken, smashed, bitten, torn and generally slaughtered in all manner of creative ways.

The titans themselves are perverse mockeries of humanity, like soulless puppets they sit firmly in the uncanny valley making them wonderfully disconcerting. Well, the usual rabble of titans do. The “specials” range from the colossus with a comically tiny head, to the female titan with all the curves you’d expect, to the titan which looks like a GI Joe doll mated with an angry Christmas elf. At times it’s difficult to take seriously while at others, the sight of these things, all fury wreathed in muscle and sinew, is breathtaking to watch.

The buy-in required to really enjoy the series is lessened thanks to it adhering to its own internal ruleset: the skyscraper walls, the cannons that point directly down, the movement gear - all totally implausible but just silly enough to be entertaining. Like the protracted but somehow rushed conversations that last half an episode (while people with itchy trigger fingers look on) that just don’t quite grate enough to fast forward past. Everything from Sawano Hiroyuki’s stirring score, laden with choral chants and the pound of war drums, through to the confident direction by Tetsurou Araki are designed to ratchet up the tension and keep you as close to the edge of your seat as possible. It’s a series that you can’t help but sit up and take notice of and, as evidenced by its popularity, a lot of people certainly have.

But it’s in between those two forces - the blunt force action and shonky character drama - that interesting elements are shaken loose.

For one, a great many people have claimed that there is a positive feminist angle to the series, specifically with the equal representation of women within the series’ military. Others argue against this, claiming that Mikasa’s unyielding devotion towards Eren is problematic, and that despite many women within the world’s military, there are none in high-ranking positions. On both sides of the argument these points are made better elsewhere so I won’t belabour them, my take on it it though is that it seems somewhat counter-productive to claim there is a feminist message when, despite the positivity of it, that doesn’t seem to be the creator’s intent. The equal, albeit slightly shallow, representations of both genders (including non-binary denominations such as Hanji) has examples of both skilled antagonists and cowardly protagonists, and means that Mikasa’s fixation on Eren being a sticking point becomes an issue with her specific character rather than an issue with the series’ representation as a whole. As for the lack of prominent, high ranking female members of the military? That’s not something I can refute from the twenty five episodes shown and would defer to those more familiar with the manga to elaborate on. What is clear though that this is a series that is entirely free of fan service and romantic subplots and despite Hajime Isayama’s use of the likeness of a questionable World War 2 figure, the series is free of a lot of dubious situations and characters that are rife in other anime.

Identifying any of the many characters doesn’t prove much of a problem when each are clearly differentiated and when the story thins the herd with judicious regularity. It serves as the series’ thematic bedrock though: layering trauma upon misery upon gore streaked battle, making every tiny victory by the human resistance eke out that much more important. Unfortunately it also serves to desensitise the viewer from ever truly empathising with specific characters. Sure the main trio and some fan favourite secondary characters (the short shall inherit the earth) are probably exempt from this culling, but once you’re taught that anyone else is fair game, it raises the question of why bother caring? It’s the very antithesis of when a story refuses to kill any characters whatsoever; here, everyone is constantly in peril and could be nothing more than a heartbeat away from death, but knowing that means being disconnected from them. For me, this culminated in the death of someone, obviously important to Jean, yet I had no idea who he was.

All that contributes to this being a survival story for humanity, so the indifference towards death is at least contextualised, especially so when we see the somber aftermath. The rotten core of society is put on display though, from the negligent monarchy out to the corrupt military police through to the layabout garrison, the fragile survey corps and finally the farmers and peasants that make survival possible. As the audience we are beaten over the head by the hubris of the gentry as much as the naivete of religious zeal which means when you are presented with someone like Eren, who doesn’t just fight for self-preservation, you more or less have to get behind him because there aren’t really any alternatives. True he may fight for revenge and he may ignore, even violently rebel against, the concerned overtures of Mikasa but he is at least different from the ingrained helplessness of the general populace.

Fundamentally the Attack on Titan anime series is just the first salvo in a franchise that has a hugely anticipated second season in the pipeline as well as a live action movie, the teaser for which made even the car commercial it joyrided on palatable. It is a modern anime sensation and a maelstrom of fan expectation. Divorcing yourself from that is nigh on impossible; even now almost a year since this first series ended, fervent posts about each new manga chapter still draw attention.

But just as there is the split between those who have and haven’t read the manga and their opinions on the series, there is the bifurcation of people who enjoy and are ardently against what the series embodies. At its core, this first anime instalment is about survival against a an unrelenting aggressor; it’s about a dervish of blades and tearing through the air on wire wings; it’s about youthful courage meeting brutal inevitability; about complacency, fatalism, foolhardiness and trembling fury. It’s not necessarily a huge amount of fun with its po-faced morbidity and pitch-black dark fantasy leanings, but it is hugely entertaining with everything spitting debris and blood and creatures punching things so hard their fist explodes.

Like Sword Art Online the popularity of it will attract the most vocal of opponents but there is a place for high octane, low maintenance shows, if not simply to attract more people to a very niche medium. It may not necessarily deserve the adoration and success it has been afforded, but neither is it the intellectual bottom of the barrel naysayers make it out as. So back full circle to my initial comment: I enjoyed Attack on Titan. Not enough to dive into the manga, but enough to look forward to the next series.

P.S. [15 September 2014]: This post contains an edited paragraph from the original post, published on 14 September 2014. After some discussion on Twitter, the paragraph on the feminist aspects and arguments with the series has been reworded for clarity. The originally published paragraph can be viewed on Pastebin.

@Feminism: I don't buy that interpretation. It's a show that has "the female titan". It felt like smurfette* all over again, where an indistinct mass of humanoids are distinguished solely by one quirk, one of which is being "female". Things like that can appear in feminist works, too, as male-defaultism is pervasive, but I haven't seen any evidence that the show is aware of that in the first place.

* This was a rather funny reversal, since I saw the show as "angry smurfs" in the fist place (with humans being the smurfs of course). There's this scene in the opening where the corps emerge over the city with their titan gear; I got a kick out of imagining smurfs rising above their little mushroom houses like that.

@ "Getting behind Eren": I couldn't. Eren's over-the-top anger puts me off so much that I'd find myself rooting for the titans, before I root for Eren. Part of that is what I spoke about above: I couldn't emotionally connect with the show for its over-the-top pathos.

But that's not quite enough to explain my antipathy. I did get emotionally invested into the simultaneously running and equally silly Mushibugyou - which replaced relentless anger with relentless optimism, and the semi-realistic style with something more cartoony. So, I think it's in part the emotion that does get the spotlight - anger - that puts me off. Angry protagonists are nothing new in shounen fighters (I think), but there's a case to be made that - as the show goes on - it re-contextualises Eren. His first gung-ho actions on the job cost a few lives, and (almost) his own. And when we get to Mikasa's backstory, he's portrayed as a borderline psychopath.

Interestingly, I think it's the character of Jean that emerges more and more as a genre-untypical avarage guy hero. It's as if the author realised that some of the typical shounen character developments (finding courage, relativising your morals) don't work Eren - and this realisation manifested as more emphais on the regular Joe, Jean. (I'm not saying that's what happened; it's just that I felt something like that going on.) I feel that Eren is and remains a psycho; it's Jean who's growing up. It's as if - in a meta narrative - Eren takes the burden of the pomp and glory (notoriety?), so that a non-protagonist can learn what it takes to be a hero.

It's as if, at some level, the show is feeling that the heroes aren't always sane (quite a few people in Erwin's troop seem a bit strange in the head), and the footsoldiers don't get enough credit. It's not that I think it's a full-blown theme; just something that lurks in the narrative waiting, perhaps in vain, to be activated.