Like many recent two-season anime series, Nagi no Asukara (lit. From The Calm Tomorrow, alt. A Lull in the Sea) is bifurcated neatly at the thirteen episode mark. You could, in theory, leave the series at that point and be content with a competent if unresolved story story of early teenage angst. It would be a huge disservice to how spectacular the series is a whole though, and though you can spend the former half playing “count how many times girls cry” each episode, the latter half exceeds an already beautiful production with a thematically rich and emotionally charged tale of adolescent love in all its forms.

It’s an unlikely recommendation for a series whose director’s previous productions have included the Inuyasha movies and the woefully unremarkable Gunparade Orchestra. Perhaps not so unlikely though for the writer who is right at home after penning The Pet Girl of Sakurasou and the similarly P.A. Works produced Hanasaku Iroha. It’s also odd to hear myself recommending it when the pseudo-contemporary setting and laser focus on romance and juvenile relationships isn’t my usual fare. But rare is a series that is afforded such startling production values that match a capable story and confident delivery.

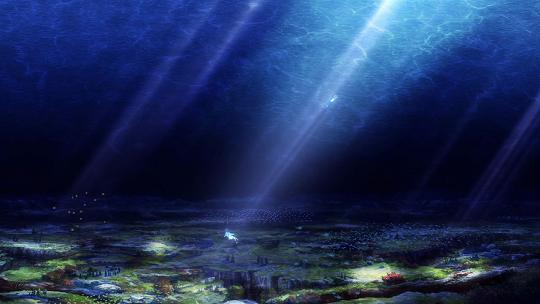

The visuals are what strike you first. Set in a working seaside town ensconced by mountains, every surface is scuffed and corroded by the ocean air with everything from boats to barriers to boxes showing signs of wear and use. Twinned with the town is an underwater village surrounded by technicolour corals and fauna and illuminated by mysterious blue spirit fire. It’s the right side of imaginative, the surface town feeling like a functioning location but on the precipice of somewhere otherworldly captured by the azure blues and faintly mediterranean architecture of the undersea village. Far from static scenery though there is a real sense of place and purpose to the setting, despite dealing with what could be the quiet demise of humanity, the series never strays from the rural environment and to its credit, never feels claustrophobic or lacking. Some of that is thanks to the stunning lighting, with everything from fiery sunsets and dawn mist to muted rain clouds and brilliant starry nights pulling the locales through seasons and time.

If the setting feels like an actual place then the character designs certainly don’t let you forget this is still anime. With expressive and almost cherubic faces that are probably eighty percent eyeballs, even the script pays homage to the depths of those eyes with beautifully florid statements like: “Your eyes are so blue, and your tears look like waves” or “These eyes… This one’s a storm” delivered without feeling out of place. Indeed likening them to the sea reveals one of the series’ key metaphors with the rolling ocean waves mirroring the feelings and emotions of the series key cast. So just as the sea roils and churns with the boatdrift ceremonies that act as the climax to each primary story arc, so too do the characters; and as the sea freezes over during the five year leap forward, so too do the characters.

That time skip, the hibernation of the people from the underwater village Shioshishio is the main source of drama in the first thirteen episodes and, for a while at least, it seems like a cheap way of forcing some Time Traveller’s Wife-esque trauma to the quadrangle of friends. That is quickly dispelled though as it is demonstrated to underpin one of the main themes: that of people changing. Whether through circumstance or the ebbing of time, vast swathes of introspection are given over to the musings of whether changing is inherently good or bad and whether a person really can change given the circumstances. It’s never applied overbearingly and the series’ does kind of wash its hands of it come the final episode with Hikari musing that, surprise, both are acceptable. Your mileage with the theme will likely hinge on how grotesque you find the phrase “You haven’t changed a bit!” when, on the face of it, the act of living is to change and especially so when applied to growing children.

That Hikari can even utter such a phrase after he starts the series as an excruciatingly annoying back of dicks is testament to how deftly character development is handled, even when applying the thinking of adults to the guises of children. So just as Hikari starts as a caustic bundle of pride and fury, Chisaki grows from demure and unassertive to conflicted and dedicated. This doesn’t apply to everyone however with Tsumugu retaining his shrewd but taciturn demeanour throughout, just as Kaname keeps his ability to make everyone he meets feel as uncomfortable as possible. More conspicuously though is Manaka who both starts and closes out the series as the chaste little princess at the centre of much of the angst that flows through the other four main characters. That’s not without its benefits though; when she awakens from hibernation her once cheery disposition is pushed to near manic limits only to be juxtaposed by a haunting, vacant quiescence.

Rounding out the cast and tipping the balance to favour females over males, are Sayu and Miuna who start out as barely out of pre-school but of age once the village folk begin to awaken from their hibernation. Their younger interactions influence their later overtures with Miuna in the thrall of Hikari just as Sayu almost literally swoons at the sight of Kaname. It’s not unexpected given the series ostensible genre but again feels like an attempt to push further drama into an already saturated situation. However it does raise the question of whether it’s possible to retain affection for someone for over five years; with Chisaki the nature of her isolation - from her friends and family - brews her conflicting feelings inside her, Sayu and Miuna have no excuse other than a tired anime trope.

Sayu at least applies some much needed sense to Kaname who has been content up until then to play the pariah and the slighted confidant while systematically attempting to raze every relationship he has. Miuna meanwhile plays a pivotal role in the grander, mythological story of the sea god and the maiden. Treated as a fairytale and analogy, it is the account of a capricious and lovelorn god and his romance with a woman from the surface. That dichotomy of surface and sea is played up in the opening episodes with racist overtones but is resurrected when children from the surface begin to develop ena, the mystical substance that allows people of the sea to breathe and talk underwater.

And eat and cry and generally treat being under the sea as like being on the surface except with a blue tint. It’s best not to overthink the physics of this as it leads down a path of wondering how the lull in the ocean happened despite the Earth still having a moon. Suffice to say that both the ena - used as shorthand for the ability to understand the feelings of another - and the machinations of the briney god are at least superficially consistent for the plot. That plot isn’t especially original with the tug of unrequited love being stretched into a conga line of angst but even after the penultimate episode, it’s still an open question as to how the series will conclude. The strength of the characters’ interactions and how skillfully they’ve been cultivated means that the bleak ending it seems to be heading for would be just as appropriate and satisfying as the happier ending that actually takes place. It transcends the usual dating game “oh who will he end up with?” question by making it about the circumstances of how they end up together rather than just who.

Even the idea of romance is questioned when it becomes apparent that after Manaka awakens, her ability to love has been taken away. It’s a shocking development and feels especially brutal given how likeable and sensitive she is but again, like the other magical aspects, doesn’t stand up to any kind of scrutiny because the series is too busy making you care about what happens to the characters to fully flesh out the mythology.

That is the lasting legacy of Nagi no Asukara and is what marks it out as something worth putting time into. That a story with no gimmick - no fanservice, no monsters at the door and no perilous chase - can present a cast that is empathetic and interesting. Fundamentally the ocean magicks - ena, the sea god, Uroko etc. - are all in service to the vivid interpersonal relationships and representative of the character’s emotional states rather than strictures for them. It is a story about a lot of things: family, love, home and loss, but it is always about people which, more than the coruscating visuals and wide-eyed designs, is why the series stands above the usual pathos parades that often populate anime. It perhaps requires more suspension of disbelief, or at least a willingness to overlook, than it could of but it rewards that with a potent and affecting drama with a memorable and, not instantly but eventually, likeable group of characters.