Six hours. That’s how long all three Puella Magi Madoka Magica movies run for, eclipsing the series run time by over an hour. You could just playlist all the series’ episodes and still have runtime spare to put up screens full of text describing what Gen Urobuchi ate for dinner when he was writing the series. A series that accumulated so much credit with so many fans that such a production would probably still be enough to line studio SHAFT’s pockets for years to come.

The backlash of course would be immense and it’s perhaps of a good thing that the three movies don’t do this lest we never hear the end of such entitled scorn. Of course when I say three movies, in reality it’s the first two movies which do this and it’s left to the third one to justify the movie franchise’s existence. I was not the greatest of Madoka’s fans when originally watching it as it aired; certainly there is a lot going on in terms of theme, pathos and direction and the pedigree behind it is obvious to see, however it was fundamentally a magical girl show regardless of its subversions or contrary tonal juxtapositions. That’s not a denigration of the genre as a whole, just a matter of taste and it not being to mine.

Its effect on fans though was defining and it generated endless discussion on whether it was a portent for anime to come - dimming the emotional lights on every series - or otherwise. It certainly put Gen Urobuchi’s name on the radar of many people and cemented director Akiyuki Shinbo’s versatility outside of the high-design kaleidoscope of Monogatari et. al. The first two movies, “Beginnings” and “Eternal”, re-tell the series with little to no deviation from the plot that was laid out in 2011. Series afficionados will likely be able to effortlessly pluck the differences from the technicolour maelstrom; but for better or worse these are essentially retouches and resequences of the series verbatim: everyone still dies when they’re meant to, everyone still cries and screams and rails against their fate until that final, defining moment that wrapped the series up in a satisfying, bittersweet bow.

The question then is what the third movie, “Rebellion”, could really add to what many, myself included, would consider a fitting ending. Surprisingly, it adds an awful lot above and beyond cash-grab fan service and the innumerable and ever expanding extended universe of Madoka fiction.

An aside first though and what probably says more about me than anything else: I could never hate Kyuubey the way many fans did; for the simple fact that there was never any malice behind his actions, only transcendental indifference much like how Lovecraft’s Old Ones are described. Kyuubey himself admitted that his species, the Incubators, are incapable of human emotion and are so technologically advanced as to make them seem, well, magical. There are blatant logical inconsistencies with the Incubators and their raison d'etre just as there is the immersion breaking revelation that magical girls are the greatest power source in the universe. Overlooking that though, his logic is unimpeachable: he does give all of the girls a choice and never willingly witholds information from them; though there is a disparity in knowledge between the two parties, it isn’t up to him to elaborate on the finer points of the deal - this is why legal professionals exist after all. “Yes I will become a magical girl just as soon as my solicitor has looked over the paperwork”.

In the same way though I never empathised with Homura and her devotion to Madoka because although compelling and emotional, Homura lost herself long before her final jump through time by losing the ability to reason beyond her crusade. It took Madoka rewriting the entirety of the universe for her mission to come to an end. Though there was that lingering “memory” of her, Homura seemed to have come to terms with the situation and found a kind of peace that she didn’t have before. That’s how the series and subsequently the first two films leave it.

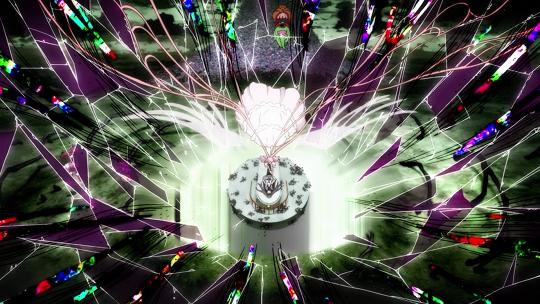

The third film then extends Homura’s single minded love for Madoka to an extreme. It stops being a mission for her to rescue Madoka from the gruesome demise of being a magical girl and becomes a mission to be with her no matter the cost. That cost is becoming Madoka, the deity’s, antithesis, forsaking all normal laws, forcibly rewriting the universe and wreathing herself in hellfire all to spend a few days with her in forced normality. It’s definitely not how the trajectory of the movie seems to be going after a happy-go-lucky opening third that sees all five featured magical girls fighting together, replete with James Bond opening-esque transformation sequences and that iconic papercraft LSD fever dream of the magical world.

It can’t last though, you know the wheel is turning and you just haven’t seen the mechanism yet. The next third sees a jaw droppingly spectacular fight between the Mami and Homura and, at its climax, what promises to be another fitting and memorable ending. Then it all gets a bit strange. It’s telling that someone else’s review mentioned a similarity to End of Evangelion because like that films latter half, this last third’s true finale is a similar cacophony of abstract imagery and confusing dialogue, hinting at but never quite clarifying what is going on. It feels dark and unsettling, like witnessing something beautiful being corrupted and being left in its wake. The only conclusion you can draw then is that Homura’s love for Madoka is almost entirely one sided with her usual imagery of gears, clocks and wastelands complemented by worshipping the statue, her ideal, of Madoka. By comparison, Madoka’s love is unconditional to the point that she sacrificed her normality to save every magical girl who ever lived and would live, it was a divine love that is then defiled by selfish whims.

That’s a lot to absorb in just shy of two hours and it’s commendable just how well the movie does it. More so than the prior two, it reflects its genesis as a screenplay rather than the usual discomfort that a series structure applied to screen exhibits. The Madoka series was no slouch when it came to visuals either; sure the characters had football shaped heads and the sketchy styling and cubist fetishism often papered over extended, static scenes of talky exposition. But Rebellion suffers none of that with all of the studio’s money up on the screen creating a dazzling monument of animation and direction, pushing turbo with the symbolism in everything from reflections and architecture to the religious symbolism, it is a creative team at the top of the pile. Kalafina and Yuki Kajiura make a similarly stunning return as well, stoking the senses with tracks that evoke everything from the heartbeat of some terrible bird to the lonely dancing of a ballerina. Very few songs could beat Kalafina’s Magia and it is used with as much verve in these films as it was in the series.

Ultimately then, the third Madoka film doesn’t change the opinion that I was left with at the end of the series. It is still a superb production and one that I have the utmost respect for because writing this bold and powerful, that you can speak about love and time travel with seriousness, is very rare. But for whatever reason, whether genre (transcendent or otherwise) or character Madoka as a franchise never ticked the “unquestioning fan” part of me that other series have. It’s strange then to say that I have very little negative to say about the three Madoka films (and most of those negatives are probably ClariS) but I cannot breathlessly and slavishly recommend them.