First released: April 2008

Version reviewed: TV

I started my Yozakura Quartet review by saying that screenshots won’t sell you on the series. I was politely reminded by both omo and tamerlane that, in not so many words, screenshots aren’t indicative of the animation of a show which for many is the real draw, over and above snapshot fidelity. (Although sometimes quite caustic, you should definitely make time for tamerlane’s phenomenal ongoing series of posts about anime and animation during years past).

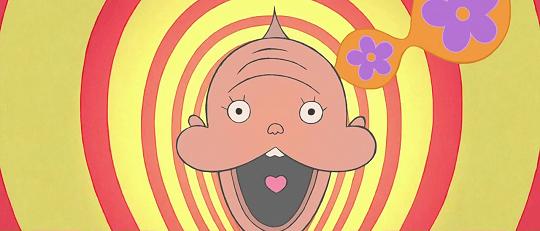

At the risk of history repeating itself then, screenshots are definitely not going to sell you on Kaiba. The same kind of sketchy, free-form line-work that I misguidedly criticised in Yozakura is here in spades, but being a Masaaki Yuasa production, that’s kind of the entire point. The animation has an endlessly pleasing sense of tactility and physicality to it and though the characters may be simplistic, almost childlike, in detail it is offset by a sense of creativity and expression that is unique and hugely alluring.

If that were all that Kaiba had going for it then it would still be something noteworthy; that subjects as diverse as family, death and identity are tackled in a scant twelve episodes elevates it to almost stratospheric brilliance.

Quite apart from the grimy cyberpunk of William Gibson or the sleek plastic-and-chrome fetishism of recent Hollywood fare, the science fiction of Kaiba is frequently laid out in the opening seconds: memories can be converted into data and transferred into new bodies, just as bad memories can be erased, good memories shared. A simple enough concept but one that opens the door to so many different aspects of life that would be altered by it. The breadth of topics the series explores is enormous and it’s telling that similarly inclined western efforts - Total Recall and Eternal Sunshine of a Spotless Mind to name only two - only deal with a limited subset of this concept.

More tangibly though, this is about Kaiba who wakes up bereft of memories and embarks on a journey to recover them. This story comprises the first half of the series and sees the body-swapping protagonist sail from world to world, persistently harried by the law, by criminals and by treasure seekers alike. The result is that each episode sees Kaiba land on a new planet, sometimes barely bigger than a hefty asteroid, and observe a new part of everyday life forever changed and now simply accepted by the ability to trade and manipulate memories.

At first it’s the bizarre: copying one’s memories into another body for one of the weirdest sexual experiences you can think of; but then it’s heartbreaking as a beautiful young girl literally sells her body to help financially support her family. One day they’ll be able to buy a new body for me, we hear the girl say. More than anything these episodes establish a lot of the lore that the series adheres to: whether that’s the devices that allow one to step inside someone’s mindscape, through to the candy-corn shaped fragments of memory that drift up out of a deceased body, sometimes caught, other times lost to galaxy spanning rivers of lost memories.

It’s stirring and hugely rewarding to watch because not only is the minutiae of life with this technology scrutinised but grander questions are astutely posed. What is mortality now the possibility of swapping bodies indefinitely is available? What of gender? Fluid at the best of times but now divorced from your physical body, even reproduction becomes a formality when designer “fashion” bodies are in vogue. Or identity, my favourite subject: do memories define the person and inform their actions? How do you know the person, the thing, you are speaking to is the person you expect? If our memories are altered, the bad removed and the good preserved, are we doomed to make the same mistakes over again? And just who does the alteration and what kind of power does that give them?

That last question is at the heart of the overarching plot and occupies the latter half of the series, delving into cults and oppression when a tool for ultimate personal control is wielded. It’s also around this point that the series becomes punishingly difficult to follow, leaping between past and present with little delineation between the two all the while weaving obscure character motivations together with the flowering of story seeds that were planted right at the beginning, when our confusion as the audience matched that of protagonist Kaiba.

What the latter half lacks though is that sense of humanity that the almost episodic opening stories had. It mixed together tales of love and loss with a kind of tragic, farcical slants that has as many hints of Franz Kafka as series antagonist Popo has of Osamu Tezuka’s Astro Boy in character design. It’s difficult not to feel a deep emotional ache when you see the scant few memories of a young girl float away into the ether, knowing that they can never be recovered and her beauty is irrevocably lost.

Sure there are elements of that as we peel away the layers of the character Kaiba, but more than anything we lose the sense of scale. The King of Memories, who created and disseminated this memory storage technology, sits with the affluent and influential on a planet’s surface while the poor and the destitute scurry below, the two separated by a toxic cloud that flays anyone of their memories upon contact. Only we’ve just been shown the rest of the galaxy with equal parts hedonism, industry and criminality so the plight of a single world and the machinations of a hypocritical anti-memory tech group seem somewhat antithetical to expectations.

Compounding this however is the climax of the series that feels manufactured rather than crafted, as if a grand peril needed to be introduced to bring the story to a satisfying close. It didn’t. Most all of the character arcs are tied off separate to this world ending jeopardy yet the conclusion still begs for interpretation in a series that, admittedly, was sometimes brutally oblique but otherwise had a cohesive plot to it.

That is a comparatively small concern though for a production that is otherwise hugely ambitious, stunningly presented and mind-meltingly creative. Kaiba demands at least one rewatch, not because of a twist that alters the perception of its earlier episodes but because there is just so much to take in. When you start an episode, there’s a fleeting sense of dissonance while your perception settles on exactly what you’re watching - whether that’s neon debauchery or pastel melancholy - but as the lilting opening track plays, you’re sucked in completely and for the duration.

More than most any other series, Kaiba isn’t for everyone. If the visuals don’t turn you off, then the story structure might, or its many pretensions or its dearth of dialogue. That’s not to say that only snobs and elitists will get the most out of the series, only that it asks a lot in return, and people watch anime for many different reasons, not always to be challenged. If none of that phases you then you have an absolute, timeless masterpiece of a series with a bounty on offer to pick at and muse over long after the final episode has come to an end.

I just found it interesting that a story about identity, love and memory is made to look like some dreamlike children's fairytale. It makes the impact of the 'serious' themes and ideas even more powerful when the entire production looks all cute, innocent and fluid. I've definitely never seen anything like it, before or since...and that includes everything else of Yuasa's that I've seen. I'm glad I'm not the only one who remembers it!